Shared risk programmes are ‘flavour of the month’ in many countries. From the United States’ accountable care organisations (ACOs) to Spain’s integrated hospital arrangements and the introduction of alternative contracting models in the NHS, passing population utilisation risk via capitated payment models to providers is much in vogue.

This is driven by an attempt to change the traditional healthcare model that operates on a fee-for-service reimbursement model and incentivises activity, to one that delivers integrated care that is centred on the patient. Such transformation is fraught with complexities that, unless implemented with care and due attention, can de-stabilise individual delivery units and the health economy at large. A successful risk contract is not one that passes the maximum risk from payers to providers, irrespective of whether they can manage that risk, but about entering into a mutually beneficial risk-sharing arrangement that promotes a sustainable health economy from a financial perspective, while providing better clinical care and outcomes for patients. In this article we share some of the considerations for both payers and providers in designing a successful risk contract and some of the pitfalls. These are mainly from the provider perspective, but it is worth reinforcing that success from a payer perspective also hinges on allowing providers to create sustainable and replicable business models.

Many hospitals and payers are negotiating new payment models

In the NHS in particular, the push for finding new payment models stems from a recognition that the Payment by Results (PbR) system has resulted in conflicting incentives for hospitals. There is little point in trying to move patient care away from hospitals with a financial reimbursement system that rewards admission. Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have neither the tools nor the resources to manage utilisation intensively in the traditional way; some are therefore looking to pass utilisation risk to their provider network (and in some cases also pass the wider health population risk).

Understandably, most hospitals are being extremely cautious in transitioning to new payment models. But shared risk agreements can be a good starting point for hospitals and other providers to transition away from PbR payment structures to populationbased payment arrangements without taking on unnecessary exposure to ‘insurance’ risks. At the same time, CCGs are keen to establish shared-savings programmes and other value-based payment models to drive incentives for health providers to meet cost savings targets, while meeting obligations to provide high-quality care. Many CCGs have stated goals in terms of the number of integrated care initiatives they are targeting to have in place over the next few years.

It is critical to understand the characteristics of the risk each party assumes

In simple terms, risk can be split into two parts: a) trend risk and b) volatility risk. Trend risk can be further subdivided into different subcategories:

- The population size risk – i.e., the risk that the covered population is larger or smaller than assumed.

- The population demographic risk – i.e., the risk that the covered population is less healthy than assumed (because it is older or has higher long-term condition prevalence than average, or a different socio-economic profile).

- Utilisation or activity risk – the risk of using healthcare services more than expected, regardless of the demographics.

- Average or unit cost risk – the risk of the average cost of the activity being higher than expected.

In a true capitation contract, the first two components are removed from trend risk, as they are compensated for via the calculation of the capitation rate. Therefore, trend risk should centre on managing utilisation and unit costs.

Volatility risk is true insurance risk and decreases as the population size increases, but is also highly dependent on the types of services being delivered. Common, low-cost services such as physiotherapy have very low volatility risk and therefore will not experience much random variation from year to year, even with small populations. Rare cancers will have extremely high volatility risk and will be subject to material changes in utilisation from year to year, unless the population over which they are spread is very large.

Fair deals often require substantial and thoughtful collaboration

When negotiating the terms of a new shared risk agreement with a CCG, it is important for providers to understand what ‘fair’ can mean and to understand the types of risks they are being asked to assume. For many, it involves care management incentive agreements rather than insurance risk transfer agreements. While it is entirely appropriate for a provider to be asked to manage utilisation risk in addition to the unit cost risk it has assumed under PbR, it may not be appropriate for a provider to be asked to manage population size and demographic risk, over which it has no means of control, or even measurement. The guiding principle is that risks should be allocated to the party most able to control those risks. If a provider is being asked to assume volatility risk, this should be clear and transparent, to enable appropriate mechanisms (such as risk pooling or commercial reinsurance) to be employed.

CCG and provider incentives should be aligned, with appropriate and realistic targets, based on an understanding of the level of clinical re-design necessary to achieve those targets. Some CCGs have been quite prescriptive in the contracting model and targets, with limited opportunity for the provider to negotiate desired refinements to the contract framework or to the detailed terms and assumptions used to populate the model. Other CCGs have facilitated workshops to design an outcomes-based contract alongside their providers almost from scratch. The level of collaboration varies significantly.

While deal concepts are often straightforward, details are almost always complex

In theory, the concept of shared risk is relatively straightforward:

- Define the attributed population

- Develop a baseline per person per month (PPPM) cost

- Mutually agree on an appropriate trend and project the baseline cost to the performance year

- When the performance year is complete, measure the actual PPPM cost

- Risk-adjust the result for population health differences (either through a simple demographic adjustment or more complex predictive model approach)

- Calculate the net savings/loss

- Apply any agreed upon adjustments for quality parameters

- Share the savings/loss

However, in practice, shared risk agreements can be incredibly complex to put together. Even the first component, the attributed population, is not straightforward for a CCG. CCGs are reliant on counts of those registered at GP practices, which may be inaccurate for many reasons, and projections based off historical census data.

The second component is also not simple for a CCG. Data systems have not been designed to report historical activity on an attributed population basis and therefore even getting accurate historical spending for the services specified in the contract can be a Herculean task—particularly when any services outside of a hospital setting are involved. Developing a baseline PPPM cost means precisely and accurately identifying the utilisation and unit cost of every service used historically over the prior one or two years for the proposed clinical specification and the exact attributed population. For example, if you are designing a musculoskeletal outcomes-based contract for the adult population, covering the entire MSK pathway, it is not sufficient to know that the CCG spent £3m on a block community physiotherapy contract last year. You must know exactly what cost is related to services proposed under the contract for those over 18 years only. In many systems around the world, these metrics are a standard part of business intelligence reporting, but this is not typically the case in the NHS.

The financial terms alone in risk-sharing programmes comprise many different and often interrelated components, all of which need careful consideration. Additionally, a prime contractor/provider1 may face additional implementation considerations such as identifying where the savings opportunities lie, how to accrue and report savings/losses in financial statements, administration of the programme, ongoing reporting requirements through the contract period, and how to divide up a surplus or deficit among the different providers and other groups within the integrated care pathways.

Many CCGs have tried to circumvent the complexity by effectively ignoring the population and demographic risk component and trying to negotiate a block multi-year contract to cover all defined services for the CCG population, with additional quality-related payments and some component of risk share/gain share. Unless the parameters of the deal are extremely clear up front, including the remedy should assumptions about population size and demography deviate materially from the initial starting assumptions, this could be a significant financial risk to the provider.

This paper highlights some of the key issues both parties should consider when negotiating a shared risk programme. The issues presented here are covered at a high level and are by no means exhaustive. The structures and terms of agreements vary significantly, there is no one-size-fits-all or off-the-shelf solution. An optimal model is one that reflects the underlying circumstances of the local health economy.

Some lessons from overseas

While many countries are experimenting with risk-sharing arrangements, the United States tends to have the most advanced contractual agreements in place and be far ahead in implementing these, which provides some useful lessons. Perhaps the most dominant consideration of any proposed agreement is the full economic impact on the health system. What might appear to be a good deal on paper (the ‘stated’ share of any surplus or deficit) might actually be something very different in practice (the ‘true’ share). Some of the components commonly included in US shared risk models are:

- Target rebasing methods

- Minimum risk corridors

- Quality adjustments

Depending on how these components are dealt with in the contracting model, it is feasible that a provider may receive as little as 20% (possibly less) of the aggregate savings over a five-year period under many ‘50/50’ agreements proposed by some payers.

Watch out for target rebasing that shifts savings to payers too quickly

Using the most recent available data to establish the following year’s cost target can shift 100% of savings to the payer in subsequent years. This can result in less opportunity for the health system to recover the initial investment used to generate savings.

Minimum risk corridors can push modest savings to payers

Intended to avoid payments that are due to random variation, this is a percentage range around the target within which there is no settlement of savings or losses. However, it can lead to a provider losing out on sharing in savings from small but consistent reductions to utilisation. Wide corridors may also lead to the payer keeping 100% of any savings. If providers are entering these agreements because they are confident of generating savings, then there is a higher likelihood that risk corridors will reduce savings shared by the provider than minimize deficits shared by the provider, which leads to potential high downside for the provider, but little possible upside.

Quality adjustments can be inappropriately biased towards the payer

Most shared risk models will incorporate a link between quality and the provider’s share of any savings/deficit. Many are structured such that the provider does not receive the full savings unless there are significant improvements in quality beyond current levels. In many standard models, quality adjustments are used to reduce the provider’s share of surplus while having no impact on the provider’s share of any deficits. This is particularly onerous for the provider if the quality targets are not realistic.

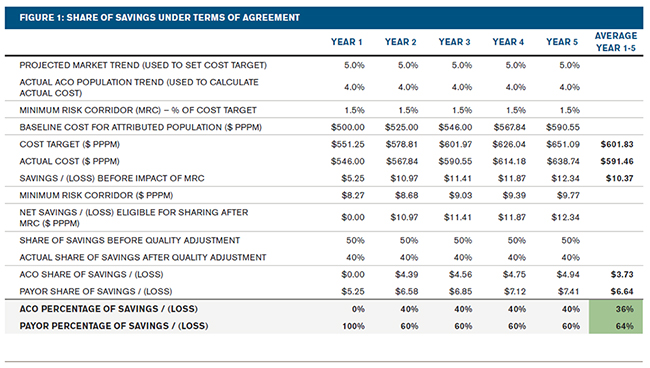

Figures 1 and 2 provide a simple illustration to demonstrate the above concepts. In this illustrative scenario, the key terms of the agreement are:

- The PPPM cost used to set the target for each year is based on the PPPM cost from two years prior (e.g., the Year 3 target is based on the Year 1 PPPM costs)

- The target is rebased each year such that the baseline PPPM cost used to set the target is the actual PPPM cost that the prime provider achieved from two years prior

- Savings and deficits are shared 50/50 (the ‘stated’ share)

- The ACO (integrated care provider) receives its full 50% share if quality measures are achieved, less if some are not fully met

- There is a minimum risk corridor of 1.5% (i.e., no savings or deficits are shared if within 1.5% of the target PPPM)

- The market trend used to set the cost target is 5% annually

The scenario further assumes the ACO achieves an annual trend of 4% over the five-year contract period, and partially meets the quality measures, resulting in it receiving 80% of its 50% share of savings.

Figure 1 illustrates the share of the savings under the terms of the agreement. On average over the five-year contract period, the ACO receives 36% of the total savings achieved (i.e., on average a $3.73 PPPM share of the $10.37 PPPM total average saving measured against the rebased cost target). The ACO’s share of available savings over the five-year period is less than the stated share of 50% because the minimum risk corridor impacts Year 1 and the quality adjustment impacts Years 2 through 5.

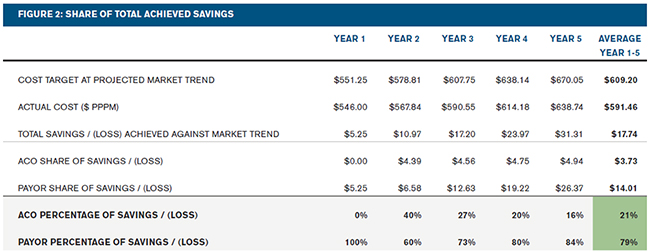

Figure 2 presents the calculation of savings using a different cost target than Figure 1. Note that for this use, cost target refers to the estimated projected costs absent any ACO intervention. Under this view, the projected costs for the entire five-year period are calculated by applying the market trends to the actual PPPM cost from two years prior to Year 1 of the agreement. This results in a larger measurement of total savings, $17.74 PPPM, than the total savings as defined in the agreement, $10.37. As a result, even though the ACO receives the same $3.73 PPPM in shared savings, this amount now represents just 21% of this alternative definition of total savings. This illustrates the adverse impact on the ACO of rebasing the agreement’s cost targets, if the ACO is able to demonstrate sustainable reductions in cost trends.

Tactics to mitigate the impact of random variation are important

Typically, utilisation of medical services will fluctuate from year to year for temporary reasons. These include short-term economic changes, flu season intensity, environmental changes, natural disasters, short-term change in birth rates, changes in medical practice, and patient behaviour. Therefore, mitigating the impact of random variation is an important consideration when developing a shared risk model. However, health systems should recognize that it will still exist, especially within programmes with smaller attributed populations. For this reason, some programmes require a minimum attributed population. The minimum size will vary from one programme to another, depending on factors such as current utilisation levels and the use of other contract terms designed to minimize the destabilising impact of random variation.

Agreements in other countries often include specific stop-loss to remove variation caused by high-cost claimants. Questions to consider are: At what level should the stop-loss be set? Are medical costs truncated at the stop-loss level or is the patient removed completely? How much cost—and what type of cost—is likely to be removed? Will it remove cost the provider believes it can manage better? Answers to these questions will differ from one health system to another and from one deal to another. Actuarial analysis can provide valuable insight to health systems in terms of the magnitude of the likely random variation. For many NHS contracts, national commissioning of specialist services will remove some of this risk, but potentially not all.

Some US agreements also carve out other high-cost cases such as transplants and major burns. A few health systems have even considered carving out the risk of increases in the birth rate of the attributed population by excluding newborns and delivery costs from their agreements.

Random variation for small populations can also be mitigated by basing the target off more than one year of past history. From the prime provider’s perspective this removes the risk of the single year used to set the target being one with utilisation levels that are lower than typical. The base point for projection can be critical in achieving the necessary cost savings.

To limit the maximum downside, some providers have also considered purchasing stop-loss reinsurance to cover overall programme risk or incorporating maximum loss provisions in their agreements with payers.

Selection of the trend assumption is critical

The selection of the trend assumption to project the target PPPM from the base period cost is clearly a fundamental and important consideration. A key question is whether it makes sense to set the target using a static trend. If so, what should that static trend be based on? A second key question is whether the trend should be market-based. A market-based trend that reflects the local historical trend for the attributed members is often the best indication for setting a target. The trend should include fee schedule or tariff increases for the health system, and, as far as possible, other local health systems too. Ideally, where applicable, the trend should include adjustments for technology and case mix, because these risks are often beyond the control of the prime contractor. The payer will be looking for the system to achieve a net utilisation trend lower than the cost curve for the market, but should not be trying to shift risk for new technologies and drugs to the prime provider wholesale.

The appropriate target trend will vary from one market to another and from one agreement to another. This is an area where actuarial scenario testing of potential outcomes is particularly valuable.

Development of the population count methodology needs careful consideration

Counting the attributed population for a capitation contract is not straightforward in the NHS. CCGs do not have an accurate count of the total population for which they are responsible, let alone an accurate count of sub-populations. Existing prime contractor arrangements rely on Exeter registration count data or census projections, where the units may or may not be coterminous with CCG geographical boundaries.

If contracts involve specific sub-populations which are diseasespecific, things become even more complex. The number of over-65s is relatively simple to estimate, but who can define what the ‘frail and elderly’ or the ‘seniors with diabetes’ population count is? To find a population with chronic diseases relies on mining primary care and prescription drug data, which is not typically available to CCGs at an individual patient level. Some methods of finding disease-specific cohorts can introduce statistical anomalies, such as regression to the mean, which can dramatically affect the savings calculation.

Many other components influence perceived fairness and financial outcome

A health system should carefully consider many other components of a shared risk model. The most common additional elements are discussed below, with key questions the prime provider needs to think through.

- Upside/downside risk and upside/downside shares: Does it make sense, and is the prime provider willing, to take downside risk from Year 1? Are the upside and downside shares equal? Other components of the contracting model will often influence the answers to these questions.

- Quality initiatives: Does this act as a threshold that needs to be met before any savings can be shared? Are the benchmark measures realistic, relevant to the attributed population, measurable, and credible? How dependent are the results to a few individual measurements? Do both the upside and downside risks get adjusted? Are the adjustments tiered (defined adjustments for meeting stepped thresholds) or continuous?

- Maximum loss: What is the likely maximum loss each year and in total over the duration of the agreement? Does the agreement have any caps on losses, or a provision to renegotiate the terms if experience is less favourable or subject to more variation than was expected?

- Risk scores: What risk model is used to adjust both base period and performance year costs? When are risk scores calculated (i.e., what run-out period is used for services which have been rendered, but which are not yet in payer reporting)? How is normalisation—the adjustment for “coding creep”—applied? What adjustments are made for any recalibration of the model between the base period and the measurement period?

- Choice of contract period: How does this impact the attributed population throughout the measurement year?

- Run-out period: When is the final settlement calculated? How much run-out is included for services which have been provided, but not yet accounted for in the financials? Is it a hard cut-off, or is an allowance made for estimated incurred but not paid services as of the date of settlement? Who prepares the final financial reconciliation and who reviews it? Consistency with the approach used to develop the target is important.

- Unforeseen events: Does the agreement include provisions to adjust the target (or any other model components) following unforeseen events, such as major changes in the population mix or size during the contract year?

- Infrastructure costs: Who pays for the cost of the health system organisational realignment that will likely be needed to implement a new model of care management? Many agreements include a contribution from the payer, sometimes called a ‘care coordination fee.’ In this scenario, the agreement should specify how that fee is included (if at all) in the shared savings calculation.

Appropriate interpretation of timely and accurate interim reports is a necessity

Reports received by the prime provider during the contract period typically seek to answer three fundamental questions:

1. Who are we managing? To be able to successfully manage the population, the prime provider needs to know on a timely basis who is in (or likely to be in) the attribution. Many providers have little business intelligence useful for population health management.

2. How are we performing? The prime provider needs to understand how it is performing against the terms of the contract. How much should the system accrue/provision for the potential likely surplus/deficit in its financial statements?

3. Where are the opportunities? The system will need to understand where the greatest opportunities for savings lie, in terms of type of service (e.g., inpatient, outpatient, professional, drugs, etc.), specialty, and leakage.

A balance will often need to be made between timeliness of information and the credibility—or usefulness—of that data. For example, information using one-month run-out periods will provide more ‘instantaneous’ metrics, but will typically involve greater uncertainty, which is due to a greater component of incurred but not reported or paid services estimates. Longer run-out periods have greater certainty but may be provided too late to be useful for decision making, e.g., a Q1 report will likely not be available until partway into Q3.

Care is also needed when interpreting reports. For example, an increase in primary or community care and/or pharmaceutical spending might initially be thought of as cause for concern.

However, it may result in fewer inpatient admissions and surgical procedures. Understanding any comparative benchmarks is also important. At a minimum the benchmarks should be appropriately risk-adjusted, reflect differences in contract payment levels, and possibly also be adjusted for a number of other components of the shared risk agreement (e.g., attribution method, any service carve outs, stop-loss, etc.).

A carefully considered model for slicing up the pie can engage doctors and incentivize success

One aspect often initially overlooked during the development of a shared risk programme is how the prime provider will divide up a surplus or provision for a deficit among the different provider and other groups that make up the integrated care system. Many attributes define a successful distribution model, but the most important is to engage and incentivise everyone to row in the same direction. Perceived fairness is key to providers’ engagement and the greater likelihood of achieving savings.

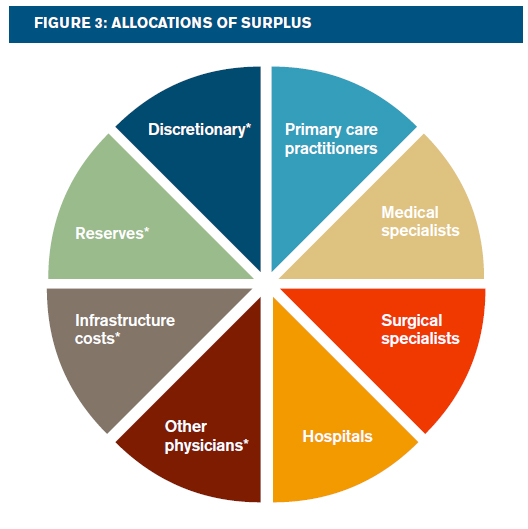

Surplus may be allocated to various individuals or groups in a number of different ways, and some may also be withheld to fund items such as infrastructure costs or future deficits (as shown in Figure 3). The slices marked with an asterisk may be ‘sometimes slices,’ i.e., they may not always receive a share of any surplus.

How big should each slice be? A traditional ‘actuarial’ approach allocates larger shares to providers that see the largest fall in PPPM costs, as it will generally be reflective of lost fee-for-service revenues from improved cost management, i.e., larger shares will be allocated to hospitals and surgical specialists. However, an ‘impact’ approach allocates larger shares to providers that have the greatest potential to improve care efficiency. This approach matches incentive with opportunity and typically allocates larger shares to primary care doctors and medical specialists. The optimal solution will vary from one health system to another, and include a number of other considerations that may be unique to each health system.

Thoughtful evaluation and appropriate financial modelling will yield well-informed decisions

Although it is clearly advantageous to develop agreements that are simple to implement and administer, shared risk programmes are complex, with many intertwined components, and significant practical implementation issues to consider. No two deals will be the same, so it is likely that one deal struck with one CCG will be very different from one struck with another CCG. Thoughtful evaluation and careful consideration is recommended, enabling prime providers and the CCG to make well-informed decisions.

These programmes are still evolving and will continue to do so over the next few years as more shared risk programmes are implemented and results begin to flow through. Prime providers and CCGs should be fully prepared for the prevalence of unintended consequences, certainly during the first year or two of the contract period. Experience from other countries indicates that a good collaborative relationship between payer and prime provider is certainly very helpful, if not essential.